We often think of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) as a modern, tech-driven solution rooted in Western culture. But the human drive for communication, connection, and self-expression is universal. From silent monks in medieval Europe to Native American tribes and Ottoman courts, people have always found ways to communicate without speech. History shows us AAC is not a modern invention, but a natural human solution to diverse communication needs. As we develop the AAC technologies of the future, we build on this humbling human legacy: balancing innovation with the power of simplicity.

Early records of nonverbal communication

Long before AAC had a name, people around the world developed their own ways to communicate without speech. You can see some examples of early nonverbal communication below.

In medieval European monasteries from the 10th century onward, monks under vows of silence relied on structured gestures to coordinate daily living.

Benedictine monks depicted in the 12th century England, gesturing to urge St. Cuthbert to accept the bishopric of Lindisfarne. Source: Prose Life of St. Cuthbert; extracts from the Historia Ecclesiastica (History of the English Church and People). © Courtesy British Library (Yates Thompson MS 26 fol 53v)

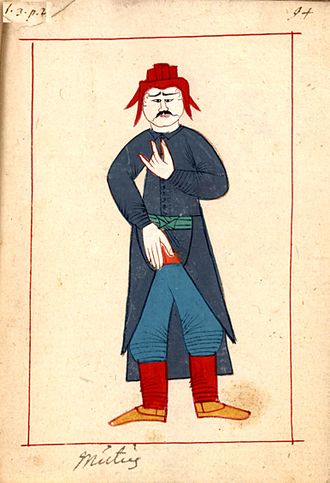

In the Ottoman Empire, between the 15th and 19th centuries, courtiers and royal attendants developed a sophisticated sign language to serve the palace’s needs. This silent communication system was used centuries before deaf education began in Europe.

Image from 1657. Representations of ‘mute’ in Ottoman Palace. Source: Public Domain, Wikipedia, Retrieved April 11, 2025.

In North America, the Plains Indian Sign Language (also known as Hand Talk) was used across many Native tribes to communicate across linguistic boundaries. There is some evidence of its existence even before European contact, and it flourished especially between the 16th–19th centuries. It was a rich, expressive language used in trade, storytelling, and diplomacy.

A newspaper illustration from Lincoln County Leader, December 28, 1900, showcasing several of the signs of Plains Indian Sign Language. Source: Public Domain, Wikipedia, Retrieved April 11, 2025.

The first formal approaches (16th–19th Centuries)

By the Renaissance and Enlightenment, Western scholars began formally studying and cataloguing methods for nonverbal communication, especially to educate the deaf.

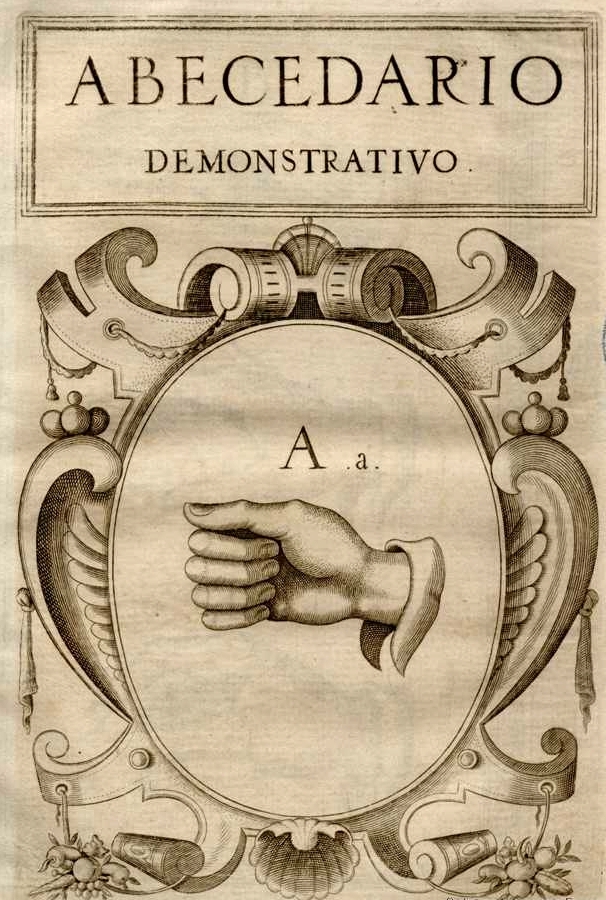

Juan Pablo Bonet’s landmark 1620 book Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar los mudos (“Reduction of letters and art for teaching mute people to speak”) was one of the first to describe a manual alphabet for the deaf.

Bonet’s illustration of the letter A. Source: Public domain, Wikipedia, Retrieved April 11, 2025.

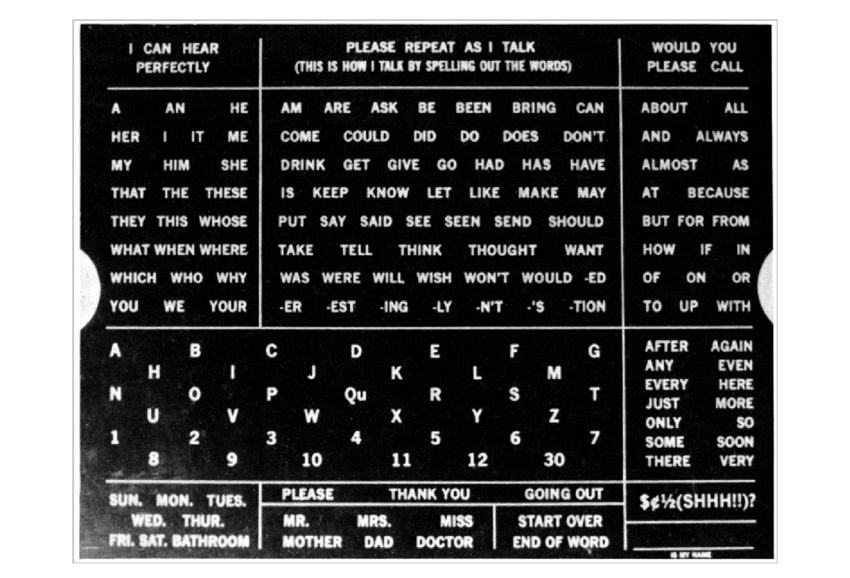

A significant milestone was the F. Hall Roe communication board in the 1920s. Hall Roe, a man with cerebral palsy, worked with supporters in Minneapolis to design a letter-and-word board to select letters or whole words. This board – printed on Masonite with notches for easy pointing – became the first widely distributed communication aid for nonverbal individuals.

The communication board used by F. Hall Roe. Source: A journey through early augmentative communication and computer access, Vanderheiden, 2003.

Symbols and speech machines: the 20th century revolution

After World War II, there was growing awareness of rights and education for people with disabilities. The second half of the 20th century brought with it a wave of innovation in both symbol systems and assistive technology.

By the 1960s, sign languages gained recognition beyond deaf communities. Programs like Makaton (developed in the UK in the 1970s) combined speech, signs, and symbols to help people with cognitive impairments communicate.

A breakthrough in the early ’60s was the Patient Operated Selector Mechanism (POSM, later known as POSSUM) developed in the UK.

A photo from the late 20th century showing a POSM user. Source: Public domain, Wikipedia, Retrieved April 11, 2025.

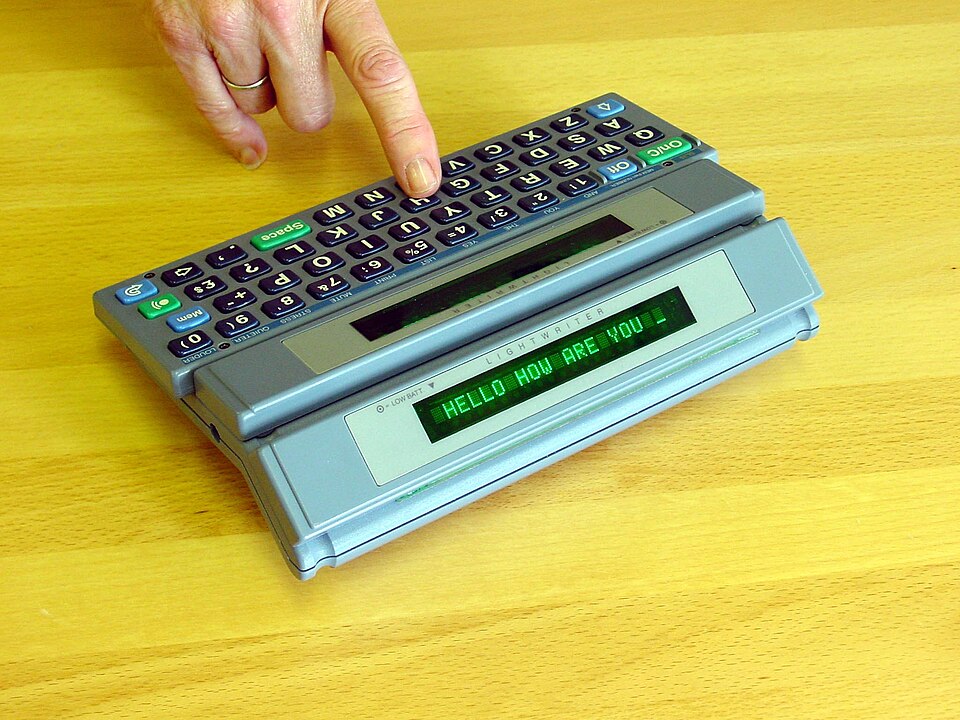

In the same era, British engineer Toby Churchill created the Lightwriter, one of the first portable devices that allowed users to type messages and have them spoken aloud.

SL35 Lightwriter. Source: Public domain, Wikipedia, Retrieved April 11, 2025.

This period marked a major turning point — AAC was no longer just paper-based. It was now powered by electricity, electronics, and speech synthesis.

From devices to apps: the new era of AAC

In the late 1990s to 2000s, Dynavox, PRC and Tobii dominated in the AAC field with dedicated devices. Slowly but surely, the early 2000s brought AAC into the digital mainstream.

In 2009, Proloquo2Go launched on the iPhone and iPod Touch, and in 2010 it became available on the first iPad — becoming a game-changer by democratizing access to AAC on familiar devices.

Smartphones and tablets transformed the landscape of AAC, offering flexibility, personalization, and — for the first time — widespread affordability. But even as AAC became more high-tech, the principle remained the same: communication must be made possible with the tools people have access to — and sometimes, the simplest tools still work best.

As we build the AAC tools of the future, human history teaches us important lessons about user-centered design. The best AAC tools are built not by chasing the latest technology, but by staying focused on the needs of the people who use them.